This note is the second in a series of research papers aiming to provide an overview of India's approach to the Indo-Pacific by focusing on the perceptions and interpretations of key Indian actors and stakeholders. Based on 45 interviews conducted in India, this project highlights the diversity of viewpoints among experts, academics, diplomats, and military officers, and offers a nuanced understanding of India’s conceptualization of the Indo-Pacific through cross-referencing subjective perspectives.

The remnants of the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia, the annual Bali Jatra festival in Odisha, and the expansion of the Chola Empire in the 11th century into present-day Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra all underscore the longevity of trade, cultural, and civilizational ties between India and its extended neighborhood, occasionally reaching beyond the Indian Ocean.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs and a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, July and August 2023. In India’s Indo-Pacific narrative, the rhetorical emphasis on this millennia-old connection between the Indian subcontinent and regions of Asia, particularly Southeast Asia,Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2018 speech highlighted that “for over two thousand years, the winds of monsoons, the currents of seas and the force of human aspirations have built timeless links between India and this region. It was cast in peace and friendship, religion and culture, art and commerce, language and literature. These human links have lasted, even as the tides of politics and trade saw their ebb and flow” (“Text of Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri-La Dialogue”,Press Information Bureau, Prime Minister’s Office, June 1, 2018). https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=179711 is embedded in a rich and diverse array of sources. This includes historical cartography, with maritime maps dating back to 500 or even 1,000 B.C., as well as cinematic and literary references.A former professor of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) even referred to the movie Life of Pi (2012), the story of an Indian boy from Pondicherry stranding on a lifeboat on the Pacific Ocean for 227 days in the 1960s (interview with a former professor of political science, New Delhi, August 2023). The early articulation of the Indo-Pacific concept by K. M. Panikkar in 1945Kavalam Madhava Panikkar, India and the Indian Ocean: An Essay on the Influence of Sea Power on Indian History, Macmillan Company, 1945, p. 109. and the writings of historian Kalidas Nag from 1941 , Kalidas Nag, India and the Pacific World, Greater India Society, 1941. which explore the cultural and civilizational linkages, contribute to a substantial body of work that describes the close ties between Indian societies and the populations of the “Far East”.See K. N. Nilakanta Sastri, South Indian Influences in the Far East, Bombay: Hind Kitabs, 1949 or R. C. Majumdar,Hindu Colonies in the Far East, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay, Calcutta, 1944. Also in the 1940s, Jawaharlal Nehru anticipated a recentering of the global strategic center of gravity from the Atlantic Ocean towards the Pacific, within which India would have a significant role. The historical and civilizational framing of the Indo-Pacific is further reinforced by speeches from regional leaders addressing Indian audiences. For instance, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in his landmark 2007 address to the Lok Sabha, drew on Indian cultural references by reinterpreting Dara Shikoh’s concept of a “confluence of the two seas”. Abe transformed this idea from its original religious context into a metaphor for the integration of the Indian and Pacific Oceans as a cohesive political and strategic space.Shinzo Abe referred here to a Sufi text titled Maima-ul-Bahrain which was written in c. 1655 by the Mughal Prince and where the author explores convergences between Islam and Hinduism, and unity of the two religions.

This political interpretation of the Indo-Pacific, although less prominent in the Indian narrative than its cultural and civilizational dimensions, permeates this collective frame of reference. Discussions frequently trace the origins of the Indo-Pacific concept to the era of European colonial expansion, when the British, French, Dutch, and Portuguese empires exerted their domination across both oceans. For others, it finds its roots in the late 1940s with the establishment of the Indo-Pacific Fisheries Council (IPFC) by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), or even in the geographical perimeter of nations participating to the 1955 Bandung Conference.Interview with a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, New Delhi, July 2023. By grouping these chronologically disparate and varied references into a unified framework, the Indian perception underscores the notion that the Indo-Pacific concept is not fundamentally new. Instead, this historical anchoring often suggests a return to a “normal” understanding of the Asian space. Echoing Nehruvian thought, some view the separation of the Indian and Pacific Oceans as an artificial division imposed first by European colonial powers and later perpetuated by the American political definition of the region.

Nevertheless, emphasizing the historical cultural, commercial, and civilizational links between the two oceans risks conflating the contemporary Indo-Pacific concept, which emerged in the late 2000s, with historical cultural and religious ties among millennia-old civilizations. This distinction must also encompass the other connections drawn in Indo-Pacific narratives with past regional experiences: the political pan-Asianism of the 20th century, the region’s deep economic and commercial interconnections, or the development of institutional frameworks for the collective management of shared resources (in the case of the IPFC). The modern Indo-Pacific concept indeed represents a political and strategic reconceptualization of the region, distinct from the previously dominant trade-centric perspective of the Asia-Pacific. While acknowledging the historical strength of connections between the two oceans, linking the emergence of the Indo-Pacific to past iterations overlooks the distinct contexts of these different eras. It fails to recognize the unique contextual anchor of the contemporary concept, shaped by the growing economic and military capabilities of China, the strategic importance of the maritime domain in global trade and economic integration, the increasing recognition of non-traditional security threats and the significant reconfigurations in the relationships between great powers and among regional actors.

While some view the transition from the Asia-Pacific to the Indo-Pacific as a “rectification of History for India”,Interview with an Associate Research Fellow on the Indo-Pacific and India’s foreign policy, New Delhi, August 2023. the reclamation of this heritage within the Indian narrative primarily serves to underscore the concept’s inherent alignment with India’s understanding of the region. This narrative approach not only facilitates the legitimization of the adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept by India, by emphasizing its continuity with Indian strategic thought and long-term regional experience; it also seeks to assert its co-production. This paper aims to go beyond the dominant narrative by examining the diversity of perceptions of the Indo-Pacific concept among key actor groups in India – diplomats, military officers, and experts or scholars. Rather than offering a comprehensive genealogy of the concept in the Indian context,For a history of the use of the concept in India, see Shruti Pandalai, “The Indo-Pacific Consensus: The Past, Present and Future of India’s Vision for the Region”, India Quarterly, vol. 78, n° 2, 2022, pp. 189-209. the study aims to identify the initial points of engagement these actors had with the term “Indo-Pacific”, assess whether these references originated domestically or internationally, and trace the evolution and diffusion of the concept within and across these groups.

A natural concept for India?

At first glance, the construction of the Indian narrative around the preexistence of the Indo-Pacific – independently of the specific contextual factors that have led to its reemergence – conveys the idea that, in India more than elsewhere, “the Indo-Pacific has always been there, but has been articulated much later”.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, July 2023. In other words, the concept preceded the terminology.Interview with a Research Fellow on South Asia, New Delhi, July 2023. This clear distinction between the Indo-Pacific as a conceptual framework for the Asian region and the Indo-Pacific as a term (i.e., the lexical manifestation of this conceptualization) is fundamental to the perception of the actors interviewed. Their accounts of the growing prominence of the Indo-Pacific in the strategic discussion in India readily fit into the broader geographical conceptualizations of the Asian region that marked the Indian foreign policy in the 1990s, notably the Look East Policy and the notion of “extended neighborhood”. Foreshadowed at the end of the 1990s under the Vajpayee government, the “extended neighborhood” referred to a vast area “from the Gulf of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca and from West and Central Asia to Southeast and East Asia”.“Speech by External Affairs Minister Shri Yashwant Sinha at Harvard University”, Speeches & Statements, Ministry of External Affairs, September 29, 2003. https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/4744 This concept continued to resonate in Indian political and strategic circles from 2004 onwards under the impetus of Manmohan Singh. While it is acknowledged that the term “Indo-Pacific” did not exist to describe these foreign policy concepts extending beyond the Indian Ocean, they serve to underline the natural compatibility of the Indo-Pacific with New Delhi’s regional strategic vision.

These references introduce a logical dimension to India’s adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept, as it fits within the continuity of the foreign policy it has pursued for decades.“It started with the Look East Policy”, a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy stated, in line with another according to whom “[i]n India, the strategic connection of the two oceans started with Rao”. In the diplomatic corps, the idea that “the Indo-Pacific was already there in India with the Look East Policy” (interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, August 2023) corroborates other views asserting that India “never had this vision of the Indian and Pacific oceans to be separate, as Japan and the Pacific Islands have always been part of the Look East Policy” (interview with a Junior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, August 2023). They align with the narrative based on intercivilizational links, emphasizing the enduring breakdown of the geographical distinction between the two oceans. This widely acknowledged continuum, particularly among diplomatic and military actors, not only enables India to demonstrate a natural dimension in its commitment to the Indo-Pacific but also serves to differentiate its approach from that of other countries, for whom the use of the term has more strategic motivations. This logic of differentiation helps to mitigate the political connotation associated with adopting the Indo-Pacific, especially in light of China’s strong opposition to the term and the initial skepticism it inspired in New Delhi’s immediate neighborhood. For instance, Bangladesh only embraced the concept in April 2023.Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, “Bangladesh: The dilemma over the Indo-Pacific Strategy”, Raisina Debates, Observer Research Foundation, November 10, 2020. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/bangladesh-the-dilemma-over-the-… Integrating the Indo-Pacific into the broader doctrine of Indian foreign policy highlights a distinction between what could be seen as India’s long-term, unconscious conceptualization of the Indo-Pacific and its more recent “first conscious use” of the term.This expression, used by several diplomats during interviews, is also found in the writings of T.C.A. Raghavan, who is himself a retired member of the Indian Foreign Service (T.C.A. Raghavan, “The changing seas: antecedent of the Indo-Pacific”, The Telegraph, July 17, 2019). https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/the-changing-seas-antecedents-of… Beyond the Look East Policy and the “extended neighborhood”, the references used to demonstrate the Indo-Pacific’s relevance to India also emphasize other significant events in India’s recent foreign policy trajectory. The launch of the Malabar naval exercise in 1992, which marked the importance of closer ties with the United States in the genesis of India’s Indo-Pacific strategy, and its temporary expansion in 2007 to include Japan, Australia, and Singapore, are key examples. In addition, the role of India, particularly the Indian Navy, following the December 2004 tsunami and the creation of the Tsunami Core Group, the predecessor of the Quad, underscores the collaboration between key actors from both the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

In this context, a former Indian Navy officer pondered: “How can we have a Look East Policy and not an Indo-Pacific policy? It would have been completely incoherent with our own foreign policy”.Interview with a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, New Delhi, August 2023. Beyond just the conceptualization, the references associated with the emergence of the term Indo-Pacific in India and its “first conscious use” also seem to dismiss the hypothesis of an external origin of the expression and therefore of its importation by strategic and political circles in New Delhi. Indeed, many interlocutors mention an Indian reference when discussing their first encounter with the term. Notably, an article by Captain Gurpreet Khurana, originally presented in September 2006 at a conference on Indian energy securityGurpreet S. Khurana, “Security of Maritime Energy Lifelines: Imperatives & Policy Options for India”, Paper presented at the India’s Energy Security: foreign, trade and security policy contexts conference organized by TERI and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS), Goa, September 29-30, 2006. organized in Goa by TERI and KAS, was subsequently published in 2007 in the journal Strategic Analysis. The article highlighted the critical role of the maritime domain in India’s energy security.Gurpreet S. Khurana, “The Maritime Dimension of India’s Energy Security”, Strategic Analysis, November 29, 2007. It was also featured in The Straits Times in the context of analyzing India’s naval strategy.Gurpreet S. Khurana, “Interpreting India’s Naval Strategy”, The Strait Times, July 16, 2007.

From narrative to perceptions: tracing the Indo-Pacific’s emergence in Indian strategic circles

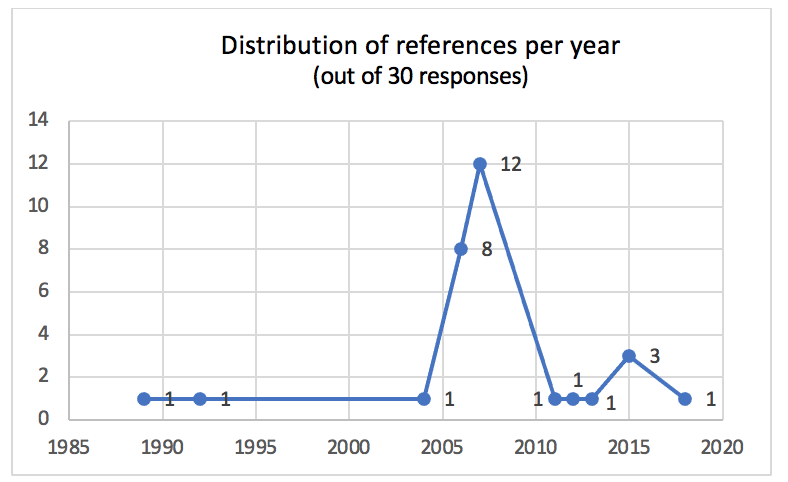

When asked about their initial encounters with the term “Indo-Pacific”, a sample of thirty actors – comprising ten diplomats, ten Indian Navy officers, and tend experts/scholars – provided a total of eleven references spanning from 1989 to 2018. The average year of first contact with the term, which also garnered the highest number of mentions (approximately 36.7 percent of responses), was 2007. For one respondent, 2007 was associated with the launch of the Quad, but for the majority, it corresponded to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s speech before the Indian Parliament, where he introduced the idea of a confluence between the Indian and the Pacific oceans. The year 2006 emerged as another significant reference point, accounting for 26.7 percent of responses; this coincides with the abovementioned publication of Captain Gurpreet Khurana’s article and his use of the term “Indo-Pacific”. Thus, for nearly 63 percent of respondents (19 out of 30), the first encounter with the term occurred between 2006 and 2007.

Source:author

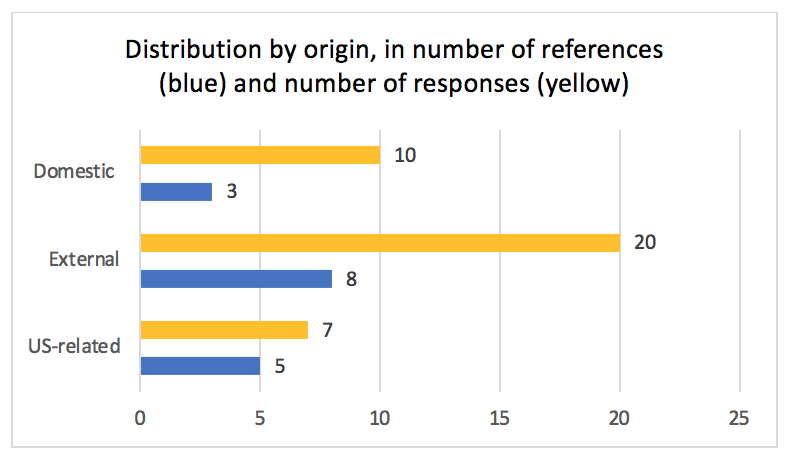

The other references mentioned by respondents present a highly diverse and mostly isolated spectrum (one response per reference), except for President Obama’s visit in 2015, which received three responses. However, it is noteworthy that approximately two-thirds of these references (eight out of eleven) pertain to external actors or refer to a partnership with external actors,Shinzo Abe’s speech at the Lok Sabha in 2007 (eleven occurrences); Obama’s visit to India in 2015 (three occurrences); in a diplomatic context in Japan in 1989 (one occurrence); through the Tsunami Core Group in 2004 (one occurrence); through the creation of the Quad in 2007 (one occurrence); Hillary Clinton’s article in 2011 (one occurrence) https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century/; Marty Natalegawa’s speech in 2013 (one occurrence) https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/fil…; and the renaming of USPACOM to USINDOPACOM in 2018 (one occurrence). whereas domestic points of contact with the term constitute only one-third of the spectrum (three out of eleven).Gurpreet S. Khurana’s article in 2006 (eight occurrences); a conference at ICWA in 2012 (one occurrence); and the launching of the Look East Policy in 1992 under Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao (one occurrence). While external references dominate, more than half of them (five out of eight, or 62.5 percent) are linked to the United States and the closer ties between New Delhi and Washington. In terms of the number of responses, however, while the balance between domestic and external references remains the same (one-third versus two-thirds), the significance of American references is somewhat moderated by the focus on Shinzo Abe’s 2007 speech, then accounting for 35 percent of the responses (seven out of the twenty external references). This still underscores the importance and the prominent role of the United States in the Indo-Pacific conceptualization of these actors.

Source: author

External references are particularly prominent in the diplomatic sector. Among the diplomatic actors, there is a total of six such references,Shinzo Abe’s speech at the Lok Sabha in 2007 (four occurrences); Obama’s visit to India in 2015 (two occurrences); in a diplomatic context in Japan in 1989 (one occurrence); Hillary Clinton’s article in 2011 (one occurrence); a conference at ICWA in 2012 (one occurrence); and Marty Natalegawa’s speech in 2013 (one occurrence). five of which are external in origin, compared to just one domestic reference (a conference organized at the Indian Council of World Affairs in 2012). Shinzo Abe’s 2007 speech accounts for 40 percent of the responses, followed by President Obama’s visit in 2015 (20 percent). These references span over 26 years, from 1989 to 2015, with the average first contact occurring around 2008. Notably, none of these references mention Captain Gurpreet Khurana’s article, which is the second most frequently mentioned reference overall. The expert community presents a slightly more diversified spectrum, with seven references out of the total eleven, including five external and two domestic.Gurpreet S. Khurana’s article in 2006 (three occurrences); Shinzo Abe’s speech at the Lok Sabha in 2007 (two occurrences); the launching of the Look East Policy in 1992 under Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao (one occurrence); the Tsunami Core Group in 2004 (one occurrence); the creation of the Quad in 2007 (one occurrence); Obama’s visit to India in 2015 (one occurrence); the renaming of USPACOM to USINDOPACOM in 2018 (one occurrence). Although these references cover an equivalent chronological range (twenty-six years, from 1992 to 2018), the average first contact with the term “Indo-Pacific” happens earlier than in the diplomatic sector, centering around 2006. Thirty percent of the responses cite the Indian author’s article from the same year, while 20 percent mention the Japanese Prime Minister’s speech the following year. The contact with the term “Indo-Pacific” among military actors, primarily from the Indian Navy, also occurred on average around 2006-2007. The responses in this category are distinctive in that they are exclusively oriented towards two references, one external and one domestic, in a perfect balance in terms of the number of responses: Captain Gurpreet Khurana’s 2006 article (50 percent) on one side, and Shinzo Abe’s 2007 speech on the other.

Beyond this distribution, the significant chronological and referential diversity within this spectrum underscores the apparent confusion between, on the one hand, the lexical usage of the term in the strategic vocabulary of an increasing number of actors, and on the other hand, a way of imagining and conceptualizing the Asian space by merging two oceans into a single strategic area. Thus, some referenced instances do not strictly pertain to the usage of the term itself, but to the conceptual prefiguration of the Indo-Pacific idea, either through cooperation mechanisms involving partners from both oceans (such as the Tsunami Core Group in 2004, the Quad in 2007, etc.), or through the enhancement of Indian foreign policy initiatives that preceded the emergence of the term (Look East Policy, “extended neighborhood”).

This brief survey of a limited sample of actors, while not claiming exhaustiveness but rather providing a general idea about the first contact of Indian actors with the Indo-Pacific, highlights two key elements: the importance of external actors in the introduction of the term Indo-Pacific within the Indian context, and the relatively recent nature of this introduction (on average, 2007). It thus demonstrates that the emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept in India is more closely tied to the political and strategic context of the region at that time and the evolving relationships between actors than to the millennia-old intercivilizational connections underpinning the official narrative.

A lexical import from external actors

While India may have shown pioneering prefiguration in conceptualizing the Asian space at various stages of its foreign policy, the usage of the term itself appears to result from strengthened contact with actors who had already been actively and publicly promoting it. This import, however, does not reflect an active effort by New Delhi to align with the evolving strategic posture of these essential partners for its regional foreign policy. Instead, most external references cited by interviewees highlight the term’s inclusive nature, which integrates India into these partners’ strategic visions, or its role in elevating New Delhi’s regional prominence. Contacts with the Indo-Pacific concept through external actors occurred either directly, through official visits to India (such as Shinzo Abe’s speech at the Indian Parliament in 2007 and President Obama’s visit in 2015), or indirectly, through the refocusing on India that these references inspired in New Delhi. For example, without changing its geographic scope, the renaming of the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) to Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) in 2018 was perceived by some as validating the growing importance of India in the American strategic framework through the integration of the Indian Ocean, in which New Delhi considers itself a central player.

These external references are rarely disconnected from the Indian context, except in specific cases related to the professional backgrounds of certain interlocutors. For example, a former diplomat who served in Indonesia cited Marty Natalegawa’s 2013 speech as a spontaneous and significant point of initial engagement with the term “Indo-Pacific”. Nevertheless, the spectrum of these external references remains largely polarized around two major partners of India: Japan and the United States. Shinzo Abe’s speech – while not explicitly using the term Indo-Pacific – referred to a “confluence of the two seas of the Indian and Pacific Oceans” and a “broader Asia” with “India and Japan coming together”.“‘Confluence of the Two Seas’. Speech by H.E. Mr Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan at the Parliament of the Republic of India”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), August 22, 2007. https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html Nonetheless, the impact of this speech within the Indian government and diplomatic community has been somewhat downplayed by some, limiting its resonance primarily to expert circles. It is precisely among diplomatic and military actors, though, that Shinzo Abe’s speech seems to have had the most significant impact. Indeed, nearly 82 percent of those who initially cited this speech as their first encounter with the Indo-Pacific belong to these categories, while experts constitute less than 20 percent.

For others, the Indo-Pacific concept is more closely associated with references related to the United States and the evolution of the U.S.-India bilateral relationship. For instance, a year after Barack Obama’s speech to the Indian Parliament in November 2010, Hillary Clinton’s article in Foreign Policy in October 2011 announcing the American “pivot to Asia” described the U.S.-India relationship as “one of the defining partnerships of the 21st century”, and acknowledged “India’s greater role on the world stage”.Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century”,Foreign Policy, October 11, 2011. https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century/ President Obama’s visit in January 2015, followed by Donald Trump’s speech at the APEC CEO summit in November 2017,“Remarks by President Trump at APEC CEO Summi, Da Nang, Vietnam”,White House (Archives), November 10, 2017. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-presi… which dedicated an entire paragraph to India despite its non-membership, further shaped the perception in New Delhi of its own importance in the United States’ regional strategy. These events also shaped the understanding of how the Indo-Pacific concept circulated in India and reflected the evolving dynamics of the bilateral relationship. This perspective has been further reinforced by the repeated official visits of American decision-makers to New Delhi on an almost annual basis in the 2010s. Beyond the presidential visit of 2015, John Kerry, Secretary of State, visited India in 2013, 2014, and 2016, followed by his successor Rex Tillerson in 2017. These visits often occurred within the framework of sectoral bilateral dialogues (such as the U.S.-India Strategic Dialogue in 2014 and the U.S.-India Strategic and Commercial Dialogue in 2016) or the signing of key bilateral agreements, such as the 10-Year Defense Framework Agreement in 2015 and the three foundational agreements in the defense sector between 2016 and 2020.Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (2016); Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (2018); Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (2020). In this context, it seems fair to say that, as one think tank expert in New Delhi puts it, “the Indo-Pacific is a lot about the U.S.” Interview with a Distinguished Research Fellow on Indian foreign policy, New Delhi, July 2023. The significance of the reinforcement of U.S.-India relations as a background factor for the emergence of the Indo-Pacific in India is also corroborated by some interlocutors who directly link the promotion of the term by the United States to its eventual adoption by India through the 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue speech.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs and a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, July and August 2023. As a former ambassador stated, “the 2015 Joint Statement is a really important landmark as a root of the Shangri-La Dialogue”,Interview with a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, August 2023. a view echoed by a former Indian Navy officer, who noted that “the Prime Minister’s speech came from Trump’s Indo-Pacific strategy in 2017”.Interview with a Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, Goa, August 2023.

The promotion of the Indo-Pacific by Japan and the United States directly to and within India has significantly contributed to its acceptance by New Delhi, further reinforced by the incremental adoption of the concept by an increasing number of regional actors, including Australia since 2013 (another Quad partner) and Indonesia. The strong resonance of these external references – even though they sometimes occurred well after Indian officials initially used the term – is closely tied to an impression of growing recognition of India’s regional significance and centrality in the Indo-Pacific by key partners in the region. For instance, a former ambassador noted that “the Indo-Pacific started with Trump, with the name changing to INDOPACOM. This included India as a vital partner. It was a signal. It means we can now get more from the US than when the Indo-Pacific wasn’t existing”.Interview with a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, August 2023. Similarly, a former Senior Official at the Ministry of External Affairs stated that “the emergence of the Indo-Pacific marked a recognition of India by the USA and others. It was the first time that India was recognized as a central player in the region”.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, August 2023. This acknowledgment of India’s central role in the Indo-Pacific by international actors underscores the strategic opportunity the concept presents for New Delhi. However, this opportunity does not imply that the concept was immediately and universally embraced within India. The following section examines the nuanced reception of the concept among Indian strategic communities, emphasizing the spectrum of agreement and divergence across diplomatic and policy circles.

Contesting narratives: the importance of non-diplomatic actors in the circulation of the Indo-Pacific concept in India

Within diplomatic circles, the dominant narrative suggests that the adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept as an official framework was largely consensual, particularly within the diplomatic apparatus. According to a former Senior Official from the Ministry of External Affairs, the minister’s office received several internal briefs during the mid-2010s, which were met with a notably positive reception. These briefs underscored the importance and relevance of the Indo-Pacific concept for India, particularly in light of China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, July 2023.This perspective is corroborated by other former diplomats, who affirmed the widespread acceptance of the term within the Indian diplomatic establishment.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, Pune, August 2023. They noted that discussions proceeded with minimal controversy, as the term had already been introduced by Manmohan Singh in 2012.Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, September 2023. Other accounts highlight more specific debates, such as those concerning the content of the 2015 joint statement and its alignment with U.S. strategy, or the 2018 Shangri-La speech, rather than the validity of the concept itself. And in fact, discussions about the acceptability of the Indo-Pacific in New Delhi are more frequently found within military and expert circles.

Several former Indian Navy officers highlight that the Indian government’s initial reception of the Indo-Pacific concept was marked by hesitation and, at times, skepticism following the Japanese Prime Minister’s 2007 speech and further on in the early 2010s. These reservations primarily stemmed from concerns about the perceived Western orientation of the concept after its adoption by the United States, as well as apprehensions about potentially antagonizing China.Interviews with a retired General/Flag Officers and a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, New Delhi and Goa, July and August 2023. Additionally, questions were raised about the extent to which the concept aligned with the expectations of ASEAN member statesInterview with a retired General/Flag Officer of the Indian Navy, Goa, August 2023. and, more broadly, about its potential political implications for India’s foreign policy in the region.Interview with a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, New Delhi, August 2023. Two main factors participate to explain why various groups within the Indian strategic community perceive the debate over the Indo-Pacific concept in India differently. First, the apparent consensus among diplomats reflects their alignment with the official narrative, which portrays India’s adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept as a natural outgrowth of historical and political trends. Second, diplomats were not the primary actors driving the debate over the concept in India. As the survey included in this article demonstrates, the term gained traction within diplomatic circles relatively late. Instead, discussions on the concept's relevance were predominantly led by experts – such as think tankers and academics—and the military, with the Indian Navy playing a particularly prominent role in its promotion and dissemination.

The role of think tanks and expert communities

Academic and expert communities have played a particularly important role as conduits for this debate, ultimately influencing political decision-makers.For a more comprehensive analysis of the use of the term in India in the early 2010s, see David Scott, “India and the Allure of the ‘Indo-Pacific’”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0020881714534038?journalCo…, International Studies, vol. 49, n° 3&4, 2014. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0020881714534038?journalCo… The discussion on the term Indo-Pacific in India was facilitated by the early proliferation of publications and conferences in Indian think tanks and universities aimed at analyzing the relevance of this emerging concept. As early as 2005, the term appeared in the journal of the newly established National Maritime Foundation (NMF, New Delhi) under the authorship of New Zealander Peter Cozens,Peter Cozens, “Some reflections on maritime developments in the Indo-Pacific during the past sixty years”, Maritime Affairs, vol. 1, n° 1, 2005. followed by the aforementioned works of Gurpreet Khurana. However, it was particularly from the early 2010s that reflections on the Indo-Pacific within Indian expert circles significantly accelerated. In 2012, C. Raja Mohan published a book examining Sino-Indian rivalry in the Indo-Pacific,C. Raja Mohan, Samudra Manthan: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific,Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2012, 360 p. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wpjb4 which coincided with a conference organized in October of the same year by the NMF, the Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis (IDSA, New Delhi), the Society for Indian Ocean Studies (SIOS, New Delhi), and the Ocean Policy Research Foundation (OPRF, Tokyo). At this conference, Mohan argued that “the Indo-Pacific Ocean is a new term and reflects the realities of contemporary Asian order”, thus supporting the message conveyed by the IDSA think tank’s press release, which described the Indo-Pacific as “a new geopolitical reality”.“Indo-Pacific is the New Geopolitical Reality”, Press Release, Manohar Parikkar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, November 1, 2012.https://idsa.in/pressrelease/IndoPacificistheNewGeopoliticalReality In 2013, the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) established a Centre for Indo-Pacific Studies aimed at better understanding the “profound shifts that are taking place around India and India’s rapidly rising stakes in the Indian Ocean and East AsiaCentre for Indo-Pacific Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University.https://www.jnu.ac.in/index.php/sis/cips;This initiative was part of a broader dynamic, corroborated by other conferences organized at the NMF, among others, and publications such as those by Nitin Gokhale for the Vivekananda International Foundation (VIF) in March 2013.Nitin Gokhale, “From Look East to Engage East: How India’s own Pivot will Change Discourse in Indo-Pacific Region”,Vivekananda International Foundation, March 12, 2013. https://www.vifindia.org/article/2013/march/12/from-look-east-to-engage…In an article, David Scott also noted the organization of three conferences on the Indo-Pacific by the think tank Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in 2014,David Scott, op. cit. along with additional publications, for instance within the IDSA.Chietigj Bajpaee, “Embedding India in Asia: Reaffirming the Indo-Pacific Concept”, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 8, n° 4, October-December 2014, pp. 83-110. https://idsa.in/jds/8_4_2014_EmbeddingIndiainAsia

The Indian diplomatic apparatus is not, however, impervious to these scholarly works. On the contrary, these conferences and publications resonate strongly within New Delhi’s diplomatic corps, which can be explained by the increasing interactions and permeability between diplomatic circles and expert communities. Some of the publications are even authored by former diplomats who held high-ranking positions within the Ministry of External Affairs and joined expert communities upon retirement. For instance, in an article in 2014, a year after retiring from his role as Secretary (East), Ambassador Sanjay Singh advocated for the Indo-Pacific as “a construct of peace and stability”.Sanjay Singh, “Indo-Pacific: A Construct for Peace and Stability”,Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, vol. 9, n° 2, 2014, pp. 100-105. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45341917?seq=1The political support provided by the Indian government for the conference organized by Indian and Japanese think tanks in November 2012 is also reflected within the Ministry of External Affairs through the significant role of its internal think tank, the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), in fostering the debate on the concept. In March 2013, the ICWA organized a conference titled Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: Asian Perspectives, during which its Director General, retired Ambassador Rajiv K. Bhatia, who co-edited a comprehensive book on the Indo-Pacific published by the ICWA in 2014,Rajiv K. Bhatia, Vijay Sakhuja, Indo-Pacific Region: Political and Strategic Prospects, Indian Council of World Affairs, 2014. On its release, the book was the subject of a conference organized by the Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies and the Jawaharlal Nehru University. https://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https:/www…described the concept as “a useful tool to understand the geopolitics of the 21st century”.“Asian Relations Conference IV on ‘Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific Region: Asian Perspectives’”, Communiqué, Indian Council of World Affairs, March 2013. https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=2&ls_id=2242&lid=1666 According to a diplomat who took part in the conference, the objective was not only to facilitate free exchanges among experts to educate policymakers on the Indo-Pacific but also to encourage them to define their own stance on the term.Interview with a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, August 2023. In such an informal context, the then-Minister of External Affairs, Salman Khurshid, already referred to the Indo-Pacific as a logical extension of India’s Look East Policy.Indian Council of World Affairs, op. cit.

The role of the Indian Navy

The Indian Navy has significantly contributed to the debate on the Indo-Pacific in India, primarily through expert circles. While think tanks and expert communities serve as the main platform for this debate, the Indian Navy has actively promoted the dissemination of the term within the Indian strategic ecosystem. Beyond the role of the National Maritime Foundation – an institution traditionally chaired by the outgoing Chief of Naval Staff – in the early strategic discussions on the Indo-Pacific, both active and retired officers of the Indian Navy have deeply engaged in debates and analyses on the Indo-Pacific. As early as July 2009, in an analytical article on the latest edition of the Shangri-La Dialogue, Admiral Arun Prakash, then chairman of the NMF, urged: “While coming on board the Asia Pacific Community would certainly bring India into the mainstream of economic and other activities in the Asia-Pacific, India’s first pre-condition (not based merely on semantics) should be to insist on having the ‘Asia-Pacific’ label replaced by the term ‘Indo-Pacific’, which has a far more geographically inclusive connotation”.Arun Prakash, “A Moment for India”, Force Magazine, July 2009. For the Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), Commodore Uday Bhaskar, then Senior Fellow at the NMF, anticipated in 2011 that “the continuum encompassing the Pacific and Indian oceans (...) will be a critical determinant in shaping the texture of the US-China-India triangle”.C. Uday Bhaskar, “Pacific and Indian Oceans: Relevance for the evolving power structures in Asia”, Queries, vol. 23, n° 6, 2011.

The influence of the Indian Navy on the dissemination of the Indo-Pacific concept in India is also evident from the widespread recognition of its pioneering role outside naval circles. For military personnel interviewed, as was stressed previously, the initial points of contact with the term are solely centered around Captain Gurpreet Khurana’s 2006 article and Shinzo Abe’s 2007 speech. However, other categories of actors (experts, diplomats), whose reference points are much more diversified, readily trace the origin of the concept in India to events in which the Indian Navy played a pivotal role. The initiation of the Malabar naval exercise in 1992 with USPACOM, signaling the rapprochement between India and the United States, along with India’s response to the 2004 tsunami,Particularly the Indian Navy’s coordination with Japan, Australia, and the United States through the Tsunami Core Group. are regarded by many stakeholders within India’s strategic circles as precursors to the emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept. As a former ambassador deployed in the region noted, “the Indo-Pacific started essentially because of India and the USA coming closer together in the naval field (…). It started with naval cooperation, when the Malabar exercise started”.Interview with a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, July 2023. For an expert on India-ASEAN relations, it is clear that “the terminology in India initially comes from the Navy”.Interview with a Senior Research Fellow on Southeast Asia and India-ASEAN relations, New Delhi, August 2023. This viewpoint is also shared by a former Senior Official of the Ministry of External Affairs, who stated: “the Indo-Pacific as a term was first used by the Navy, because it is the only public body to have capacities at sea”. Interview with a former Senior Officer of the Ministry of External Affairs, Pune, August 2023. While the Indian Navy does not claim authorship of the concept, its early usage among naval circles is naturally justified by the fundamentally maritime dimension of the Indo-Pacific. Interview with a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, Goa, August 2023. For these actors, the adoption of the term reflects a logical evolution and appears more widely accepted, in contrast to the hesitations within India’s diplomatic circles in the late 2010s, which were primarily driven by concerns over antagonizing China.Interviews with two retired General/Flag Officers of the Indian Navy, New Delhi and Goa, July and August 2023. Therefore, the Indo-Pacific concept is, according to a former Chief of Naval Staff, the natural evolution of a longer processInterview with a retired Senior Officer of the Indian Navy, Mumbai, August 2023. grounded in already established naval interactions with actors from both oceans.

This maritime dimension and its natural alignment with the operational environment of the Indian Navy are insufficient alone to explain its influence on the emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept in India. However, it corroborates a broader phenomenon: the increasing importance of the Indian Navy’s role in Indian foreign policy. In this context, the Malabar naval exercise, and even more significantly, the Indian Navy’s pivotal role in the response to the 2004 tsunami, are perceived as symptoms of a gradual recognition in India of the Indian Navy as a tool of foreign policy.Interview with a retired General/Flag Officer of the Indian Navy, New Delhi, July 2023. In that sense, the growing involvement of the Indian Navy in diplomatic engagement with regional countries positions the Indo-Pacific concept as a key instrument for enhancing its own role and contribution to India’s foreign policy.As was highlighted in six interviews with two retired General/Flag Officer (in New Delhi and Mumbai, July and August 2023) and four Senior Officers (in New Delhi, Mumbai, Goa and Pune, July and August 2023). It is noteworthy that the term Indo-Pacific appears six times as early as 2015 in the maritime security strategy published by the Indian Navy, thereby formalizing for the first time in an official Indian document “the shift in worldview from a Euro-Atlantic to an Indo-Pacific focus”.Indian Navy, Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy, Naval Strategic Publication, 1.2, October 2015, p. 3. In this region, where the Indian Navy positions itself as “a ‘net maritime security provider’”, particularly in India’s immediate neighborhood,Ibid., p. 8. the Western Pacific and its coastal regions are included in the Indian Navy’s secondary maritime areas of interest, following the southeastern segment of the Indian Ocean.Ibid., p. 32. Although the term Indo-Pacific is not explicitly mentioned, the 2009 Maritime Doctrine already introduced the Western Pacific within the geographical scope of the Indian Navy,Indian Navy, Indian Maritime Doctrine, Naval Strategic Publication, 1.2, 2009, p. 68. breaking away from previous concepts extending from the East African coast to the Strait of Malacca. By formalizing the term Indo-Pacific, the 2015 document expresses a renewed ambition to “shape a favorable and positive maritime environment”, aligning with the foreign policy objectives set by the SAGAR initiative a few months earlier.These are listed in a table on p. 78 of the document.

Conclusion

The gradual acceptance of the Indo-Pacific concept in India and its dissemination within Indian strategic circles does not appear to have followed a linear or uniform process. On one hand, the mirror effect caused by the geographical correspondence of the current concept with earlier frameworks which have significantly shaped India’s foreign policy in the past has undoubtedly contributed to its strong acceptability, almost instinctive in the Indian context. This correspondence is also fundamental to the narrativization of the Indo-Pacific beyond any political and strategic meaning, encompassing historical, cultural, and civilizational references that support the claimed naturalness of this vision for India while contrastingly antagonizing the distinction between the two oceans as artificial and of Western origin. India’s “Indo-Pacific predisposition”Interview with a former Ambassador who served in the Indo-Pacific, New Delhi, August 2023. not only reaffirms the historical economic and cultural influence of the Indian subcontinent across the Asian region – a perspective that contrasts with the Asia-Pacific concept, which was centered on East and Southeast Asia and driven primarily by economic considerations – but also contributes to depoliticizing the Indo-Pacific concept amid its contemporary proliferation.

The significance of these contextual evolutions in the emergence and circulation of the term Indo-Pacific, as it is understood today, is particularly evident through the influence of external references in the introduction of the term in India and their role in its gradual expansion in the Indian context. Thus, India’s adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept, initially encouraged by expert circles and the Indian Navy, also serves as a means for New Delhi to signal convergences with key partners (the United States, Japan, as well as Australia, Indonesia, and subsequently the entire ASEAN) in response to changes in the regional strategic environment. However, this approach is largely influenced by a reassessment of India’s importance by these actors, particularly the United States, in relation to New Delhi’s role within the vision they promote for the Indo-Pacific. As highlighted by a former Foreign Secretary, as well as many other interviewed actors, “India [is] no longer at the margins of Asia but almost at the center. What changed between Asia-Pacific and Indo-Pacific is the ‘Indo’. And ‘Indo’ means India”.Interview with a former Foreign Secretary of India, New Delhi, August 2023.