Sommaire du n°20 :

In today’s complex global landscape, building strong partnerships is more essential than ever. The Brazilian National Defence Strategy prioritises strategic partnerships with other countries to accelerate defence production, reduce dependence on critical component imports, encourage technology transfer, and ensure greater national autonomy (Brasil, 2020). Thus, offset can play a vital role in Brazilian defence industrialisation, making it crucial for interested observers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Offset practices in Brazil are governed by a formal policy, which imposes a range of ‘legal’ requirements in the process of defence acquisition, including mandatory offset commitments on foreign vendors whose sales have a minimum net value threshold (Free on-Board price - FOB) of $50 million (USD). This article aims to analyse this regulatory offset policy framework and provide key points for reflection. It presents partial findings from a doctoral research project focused on the practice of offsets in the country.

The Offset Regulatory Framework

In Brazil, the offset regulatory framework is composed of regulations issued by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), as well as specific regulations established by each branch of the Armed Forces. The MoD regulation provides strategic guide-lines, objectives, and concepts, and outlines the set of permitted offset modalities. Additionally, the MoD designates that each branch of the Armed Force is responsible for implementing the offset policy. As a result, each service has developed its own regulations addressing the negotiation, implementation, and monitoring of offsets.

Brazil’s MoD regulation highlights flexibility in negotiations The article 8, sole paragraph of Normative Ordinance 3.990/2023 (Offset Policy) provides that “the rules for negotiating offset agreements must allow for a degree of flexibility that considers the unique characteristics of each import process in order to achieve the objectives defined in this Policy (…)” (free translation). However, it is important to make a distinction between the idea of flexibility that enables tailored approaches for each specific offset deal and the existence of different perspectives that may lead to misunderstanding. For example, each military branch can establish its own parameters for multiplier factors, analysis methodologies, credit awarding, and banking systems. This diversity of perspectives can create confusion and a lack of clarity during the proposal and negotiation phases of offset projects. While the complex context of offsets requires flexibility to foster innovative solutions, clear guidelines are essential for ensuring effective collaboration and understanding among participating parties.

Brazilian Offset Policy Evolution

The first regulation establishing a formal offset policy in Brazil was issued in 2002 (Normative Ordinance 764/2002) and then replaced by the 2018 regulation (Normative Ordinance 61/2018). In 2021, another regulation was issued (Normative Ordinance 3,662/2021) and later replaced by another one from 2023 (Normative Ordinance 3,990/2023), which is currently in force. Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of offset policy development.

While Brazil’s first national defence offset policy was established in 2002, the practice of offsets dates to the early 1950s when the Gloster Meteor fighter was acquired from the United Kingdom. The acquisition was distinctive because it entailed the use barter; that is, Brazil paid for the fighters by trading the equivalent value in cotton. (Modesti, 2004, as cited in Correa, 2017). Moreover, some internal and isolated offset rules can be traced back to the early 1990s in the Air Force and the early 2000s in the Navy. This begs the question as to why a formal and comprehensive offset policy only emerged in 2002? The historical political and economic context is able to provide some insights in this regard. According to Melo (2015), the 1990’s post-Cold War era, brought significant downsizing of the defence market, and Brazil suffered a sharp decline in defence exports, a shrinkage in defence spending, and an absence of defence-related long-term projects and policies.

This downward trajectory persisted until the early 2000s, when a new economic environment enhanced the state's investment capacity across various sectors, including defence. In this more favourable climate, a series of initiatives emerged to establish an institutional and legal framework aimed at strengthening Brazil’s defence industry (Melo, 2015). A key milestone during this period was the establishment of the Brazilian Ministry of Defence in 1999. Additionally, the introduction of Law 136/2010, known as the 'New Defence Law,' significantly strengthened the MoD's role by assigning it responsibilities for defence procurement, enabling a more coordinated and strategic approach to defence acquisition context (Uttley, Moreira, Medeiros, 2022). Importantly, the framework also laid the foundation for the development of an integrated offset policy within the MoD, enhancing coordination and bringing greater clarity to offset practices.

The development of offset regulation has exhibited two major features: firstly, there was a 16-year gap between the establishment of the offset policy in 2002 and its first modification in 2018; and secondly, there has been a significant increase in regulatory modifications from 2018 to 2023. To evaluate the reasons behind these features, Figure 2 illustrates the overlap in timelines of (i) public policy influencing offset practice, (ii) relevant defence projects, and (iii) TCU (Brazilian Federal Audit Court)The Brazilian Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União – TCU in portuguese) is a constitutional body responsible for overseeing the federal government's financial management and plays a crucial role in defence projects. The TCU ensures that funds allocated for defence are used appropriately and in compliance with legal standards by examining contracts and expenditures. Additionally, it assesses the effectiveness and efficiency of defence programs, evaluating whether intended outcomes are achieved and whether resources are utilized effectively. The TCU's decisions can lead to sanctions or corrective measures. reports related to referred defence projects.

Figure 1: Timeline offset regulatory development

Source: Author, 2024

Figure 2: Timeline overlap

Source: Author, 2024

Understanding the 16-year gap

As previously mentioned, the 2000s marked the beginning of Brazilian defence industrial reconstruction that included features critical to the development of offset in the country:

- ‘Establishment of Key Policies’. The 2005 revision of the Defence National PolicyThe National Defence Policy is the principal strategic document guiding the planning and implementation of actions related to Brazil’s national defence. In 1996, the Defence National Policy was approved, marking the first initiative to unite the efforts of Brazilian society on the issues of defence and national sovereignty. The policy was updated in 2005 and revised again in 2012, when it was renamed the National Defence Policy. Since then, a periodic review of the policy has been stipulated every four years. and the 2008 First National Defence Strategy, with the latter organised around three structured axes, namely, the reorganization of the armed forces, the restructuring of the national defence industry, and the composition of the Armed Forces. The second axis aims to ensure that the Armed Forces’ equipment needs are supported by technologies under the national domain. In this sense, the above planning documents highlight the risk and vulnerability of ‘not’ using offset in defence acquisitions (Brasil, 2008). These hi-level documents also emphasize the relevance of government procurement power as a strategy to achieve national defence goals.

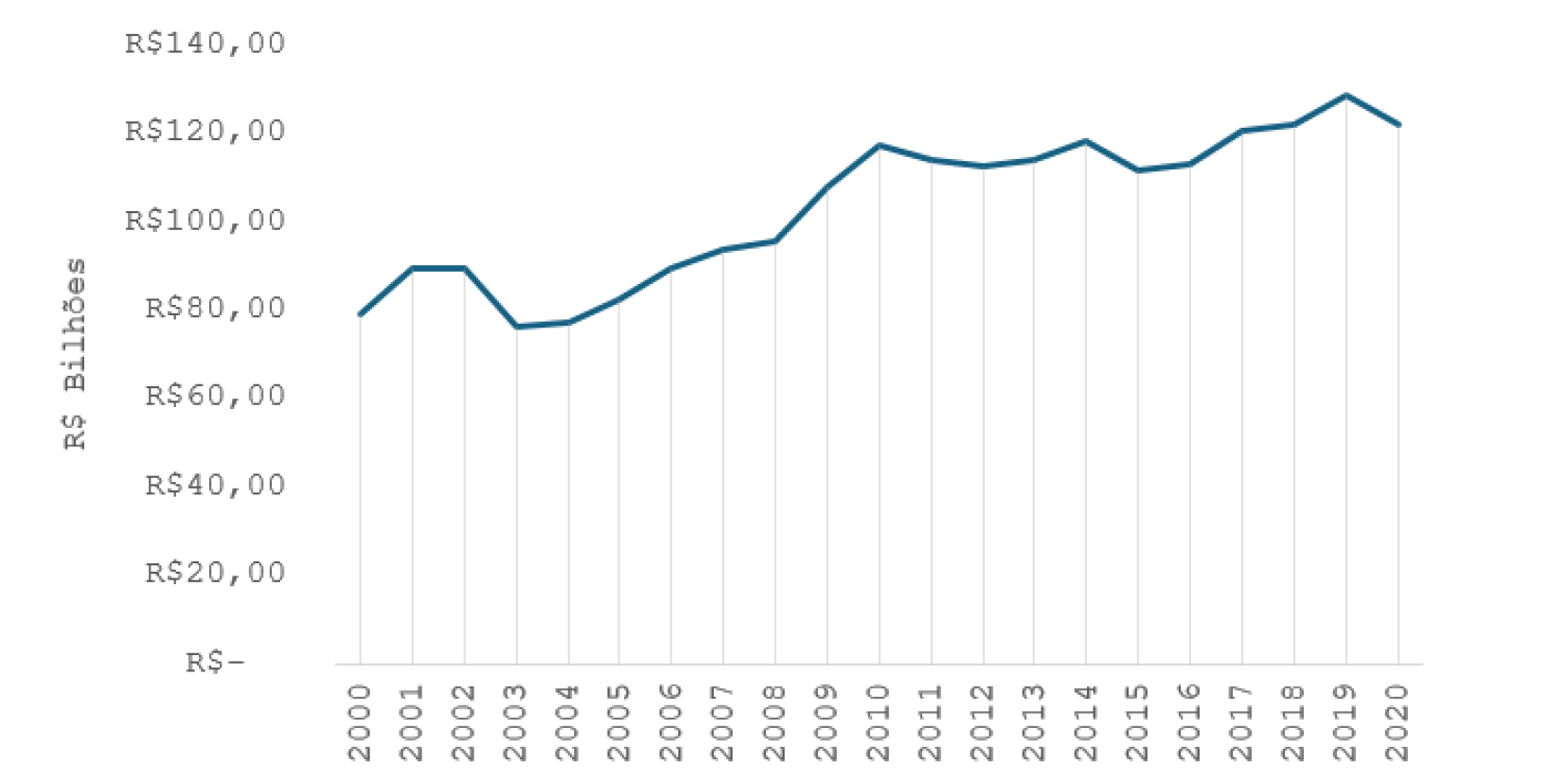

- ‘Increased Investments’. Driven by the National Defence Strategy established in 2008, there was in the ensuing year a significant rise in investments aimed at modernizing military capabilities (Matos, 2024), as illustrated in the graph below (Figure 3).

-

‘Regulatory Developments’. The introduction of a growing number of regulations related to innovation, technology, and defence acquisition has played a key role in driving discussions on necessary reforms. Notable examples include the Innovation Law of 2004 and the Defence Procurement Law of 2012, which established special rules and incentives for acquiring defence products. For instance, Law 12.598 introduced significant innovations, such as:

- (i) EED (Empresa Estratégica de Defesa): This designation is granted to companies deemed essential to the national defense sector. To qualify,a company must register with the Ministry of Defence and meet specific criteria, such as having its registered office in Brazil, demonstrating proven scientific or technological expertise within the country, and ensuring control of shares by Brazilian nationals, while allowing for foreign capital participation.

- (ii) RETID (Regime Especial Tributário para a Indústria de Defesa): The RETID is a special tax regime that provides tax incentives and exemptions to businesses and products engaged in defence industry activities.

- ‘Emergence of Strategic Defence Projects’. The economic and political environment described above led to the start of several significant defence projects between 2006 and 2010, including the: (i) FX-2 project, relating to the Gripen fighter jets, with the aim of renewing Brazil's fighter fleet; (ii) Prosub - Submarine Development Programme, a strategic initiative aimed at modernizing and expanding the Brazilian Navy's submarine fleet; (iii) Sis-fron - Border Monitoring System designed to enhance the security and surveillance of Brazil's borders; (iv) HXBR - Helicopter Programme, aimed at modernizing the Brazilian Army's aviation capabilities; and (v) KC-390 - aircraft development project aimed at modernizing the Brazilian Air Force (FAB) fleet.

These milestones collectively contributed to the development of a more strategic approach to Brazil’s defence acquisition landscape, and a corresponding impact on the use of the offset mechanism. Yet, why did the first offset policy update not occur until 2018? Importantly, the maturation and organizational development of Brazilian MoD unfolded only gradually over the course of the 2000s. Nevertheless, the experience gained from offset projects along with the associated defence programmes played a crucial role in informing the offset debate. Finally, evaluation of offset projects by the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), along with the subsequent recommendations, directly shaped the evolution of offset policies. These reports carry significant weight in Brazilian public administration and highlighted critical vulnerabilities in the practice of offsets.

Figure 3 - Budgetary Evolution of the Ministry of Defence in Brazil (2000-2020)

Source: Matos (2024, p.145), based on data from the Integrated Planning and Budgeting System (SIOP)

Understanding the significant increase in regulatory modifications from 2018 to 2023

As outlined earlier, several factors have shaped the evolution of offset regulation: the increasing number of defence projects, the expansion of regulations related to defence acquisition and the experience gained from ongoing strategic defence projects. However, a key factor significantly influencing changes to the offset policy after 2018 has been TCU reports. A comparative analysis between these reports and offset regulations clearly demonstrates that policy changes have sought to address TCU's recommendations and risk alerts. Two examples are provided below:

1.TCU Report nº1848/2020Tribunal de Contas da União. Processo de Auditoria de Conformidade - TC 039.879/2020-8. Acórdão nº 1848/2022 – TCU – Plenário. Available in: Pesquisa textual | Tribunal de Contas da União., recommends: "9.3.2. instruct the Singular Forces to include in their projects involving offset agreements the carrying out of risk assessment studies regarding the continuity of the beneficiary companies after the end of the term of the respective offset agreements, to promote the increase of nationalization and the progressive independence from the foreign market” (free translation). In response to this recommendation, Article 18 of the 2023 offset policy stipulates that contracts must include: “IV – [...]clauses that require the performance of risk assessment studies by the contracted company, in order to identify and mitigate potential risks that may affect the continuity of the benefits arising from the compensations, after the end of the respective offset agreement” (free translation).

2. A particular concern has been raised over the transfer of technology to subsidiary companies from the same economic group of the offset provider. Saunders (2023), analysing TCU reports on the PROSUB and HXBR projects, highlights that the Brazilian audit court identified that some European industries had created Brazilian subsidiaries specifically to receive technologies transferred via the offset project. This suggests technology from a vendor company was transferred to its own Brazilian subsidiary operation, which thus remained under foreign ownership. In the same re-port TCU argument that only companies certified by the Brazilian MoD as ‘Strategic Defence Companies’ should be accepted as recipients of technology transfer. This issue is also directly addressed in Article 20 of the 2023 offset policy, as will be discussed later.

A key consideration for future reflection will be to assess whether proposed modifications to the offset policy effectively address the risks identified by the TCU. Alternatively, it may be necessary for the Brazilian government to engage in a broader dialogue that includes representatives from various sectors, beyond the MoD and the Armed Forces. This broader discussion could help identify comprehensive solutions to the challenges related to technology transfer, industrial development, and Brazil's national defence goals.

Main changes in Offset Policy between 2002 and 2023

A comprehensive comparative analysis has been conducted by the author, revealing significant changes between 2002 and 2023 offset policy. The relevant changes that may indicate shifts in the interpretation of offset practices in Brazil are illustrated in Table, below, showing the original writing of relevant concepts and their respective modification.

Some of these modifications were selected as key points for debate:

A question can be raised over the Offset Policy Name. In 2002, the offset policy was known as the Commercial, Industrial, and Technological Defence Compensation Policy. However, with the introduction of new regulations in 2018, the policy was renamed the Technological, Industrial, and Commercial Defence Compensation Policy. This change prompts the question as to whether the repositioning of the term "Technological" was intentional. If so, does it point to Brazil's preference for technology offsets? Analysis of the public policy framework as well as consideration of other modifications to the offset policy, suggest that the change in policy name was not random but reflects Brazil’s preference for technology-related offsets.

There were also issues regarding the nature of the Offset Provider. Brazil’s offset policy clearly stipulates that the offset provider is the foreign supplier. However, what happens in the case of a consortium and special purpose company (SPC)? The 2021 regulation provides that in such cases, the obligation for offset may rest with the consortium or SPC. Yet, a detailed analysis of offset policy (and its supporting documents) makes clear that a Brazilian company which is part of a consortium or SPC has joint and several liability only in relation to the non-fulfilment of the offset obligation by the foreign supplier (which remains as the “first” offset provider).

Similar concerns exist over interpretation of the term, “offset beneficiary”. The 2018 regulation recommends the enrolment of science and technology institutions (ICT) as well as universities, as beneficiaries of offset projects. The 2023 regulation also introduces important changes that must be high-lighted. It provides that, whenever possible, the beneficiary company should not belong to the same economic group as the foreign offset provider. This provision clearly reflects Brazil's concern with the absorption and retention of transferred technologies, as highlighted in the reports by the Brazilian Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), as previously mentioned. While the new provisions of the 2023 offset policy address the TCU's concerns, it is important to recognize that these are defence technologies, subject to strict protection and regulation. In some cases, transfer is only allowed if it occurs within the same economic group. Therefore, the phrase 'whenever possible' should be carefully considered; it must be understood that transferring technology to a company within the same group is not prohibited by offset regulations, and each case must be assessed individually.

Finally, greater clarity has been called for over offset provider obligations. The 2023 regulation introduces a significant innovation, which provides that the offset provider must: (i) indicate the beneficiary company and certify its skills (ii) demand from the beneficiary a knowledge management (KM) programme, and (iii) conduct a risk analysis to identify and mitigate risks that may affect the production of offset results. This innovation merits reflection: even if these three items are perfectly executed, is it enough to ensure the correct absorption, retention and dissemination of knowledge is acquired within Brazilian territory? It is important that effective risk management is applied across all project phases, from the planning stage to the control phase (Saunders, 2023) and therefore it must be conducted by all stakeholders involved in the offset operation.

Figure 4: Offset Regulatory Evolution Analytical Table

Source: Author, 2024 / Caption: ○ original writing ● modification

Closing Perspectives on Brazilian Offset Practice

As observed, the evolution of Brazil’s offset policy reflects the country’s growing attention on this policy tool, with a particular emphasis on the acquisition and development of technology. It has also become evident that offset regulation has increasingly been used as an instrument to address challenges in technological development, such as those related to absorption capacity and technology retention. However, it is crucial to recognise that the offset policy, by itself, is insufficient to overcome these challenges. Believing that tightening the regulations will resolve these issues is not only a misconception but may also hinder the creative use and implementation of offset projects that could genuinely benefit the country. A well-structured and coordinated public policy framework is essential to effectively address this challenge. Moreover, it is undeniable that social and economic factors play a significant role in shaping public policy. In this context, understanding the Brazilian offset perspective requires broader analysis, encompassing not only the logic and dynamics of defence acquisition, but also societal perception as to their value, indeed, even necessity. In this regard, there remains considerable opportunity to deepen the discussion on Brazil’s offset strategy, in a bid to identify lasting and effective solutions capable of overcoming existing challenges, while ensuring a clearer alignment between offset practice and the national defence objectives and priorities.

References

Andrade, Israel. O. Base industrial de defesa: Contextualização histórica, conjuntura Atual e perspectivas futuras. In: ABDI - Agência Brasileira de Desenvolvimento Industrial; Ipea - Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Mapeamento da Base Industrial de Defesa. Brasília, 2016.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. Livro Branco de Defesa Nacional, 2020.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. PND, 2020 Política Nacional de Defesa.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. Portaria Normativa N° 764/GM-MD, de 27 de dezembro de 2002.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. Portaria Normativa N° 61/GM-MD, de 22 de outubro de 2018.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. Portaria Normativa N° 3.669/GM-MD, de 27 de dezembro de 2021.

Brasil, Ministério da Defesa. Portaria Normativa N° 3.990/GM-MD, de 3 de agosto de 2023.

BALAKRISNAN, Kogila. Technology offset in Defence Procurement. New York, NY: Routledge, 2018.

Correa, Gilberto Mohr. Resultados da Política de Offset da Aeronáutica: Incremento nas Capacidades Tecnológicas das Organizações do Setor Aeroespacial Brasileiro. Dissertação de mestrado – Curso de Ciências e Tecnologias Espaciais, Área de Gestão Tecnológica – Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica. São José dos Campos, 2017. 152f.

Heidenkamp, Henrik; Louth, John; Taylor, Trevor. The Defence Industrial Triptych: Government as a Customer, Sponsor and Regulator of Defence Industry. RUSI. Whitehall Papers. 2013.

Matos, P. O. Análise dos recursos das forças armadas e do Ministério de defesa. In: Santos, Thauan; Leske, Ariela Diniz.Economia de Defesa: aportes teóricos, novos temas e o caso do Brasil. 1. ed. – Curitiba: Appris, 2024.

Matthews, R. The Political Economy of Defence. Cambridge, United Kingdom; Cambridge University Press, 2019

Matthews, R., Anicetti, J. (2021). Offset in a Post-Brexit World. The RUSI Journal,166(5), 50–62.

MELO, Regina de. Indústria de defesa e desenvolvimento estratégico: estudo comparado França/Brasil. Brasília: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão, 2015.

Saunders, S.R.L. A gestão de riscos em face dos contratos de compensação tecnológica nas forças armadas. 2022 164p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Direito) - Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília – Brasil (2022).

Uttley, Matthew R.H., Moreira, William S., Medeiros, Sabrina E. Welfare gains in the Maritime Domain. A comparative analysis of defence industrial policies and shipbuilding in the United Kingdom and Brazil. In: Kennedy, G., & Moreira, W.D.S. (Eds.). Power and the Maritime Domain: A Global Dialogue (1st ed.). Routledge, 2022.